He died on the evening of what we would call the 25th, but in ancient times, the Day changed at dusk. So for his contemporaries, he died on 26th May. But, as he shares his day with St Augustine, some celebrate the Venerable Bede on May 27th!

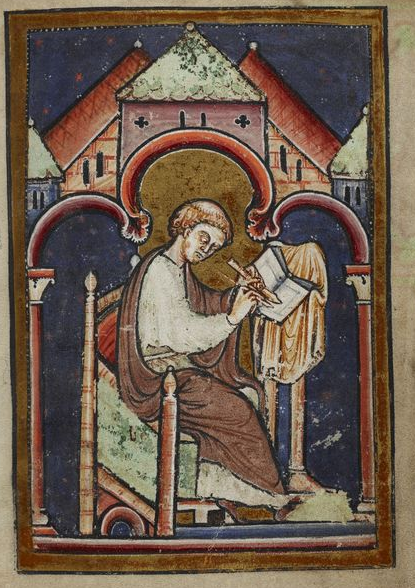

Called the Father of English History, the Venerable Bede was an excellent historian, who set the tone and standard for many centuries of English Historiography. He is mostly remembered for the ‘Ecclesiastical History of the English People’ which provides the most trusted account of the events of the Post Roman, Migration, and Anglo-Saxon periods.

So well regarded is he that he is the only Englishman mentioned in Dante’s Paradiso. This is the third part of the Divine Comedy. The other parts are about the bad people in Hell and Purgatory. Bede is with the Angels in Heaven.

He is Venerable not only in the general sense of being wise, old and respected, but also in the technical sense:

‘(in the Roman Catholic Church) a title given to a deceased person who has attained a certain degree of sanctity but has not been fully beatified or canonized.‘ (Oxford Languages)

In 1899, the Catholic Church honoured him with the title of Doctor of the Church – someone holy who had contributed to the theology of the Church.

He is considered by some to be the best historian in olden times, only equalled by Herodotus (said Thomas Carlyle). Thucydides surely says I! (Note: Herodotus is known as the ‘Father of History’ for his storytelling and breadth of the scope of his attention. While Thucydides didn’t tell tales, he concentrated on empirical evidence and so is known as the Father of Scientific History)

Bede is so good because he checked his sources and had access to a wide range of books. He even had a line to the Vatican so he could check his facts with Vatican records. This in the 8th Century! The Venerable Bede is the polar opposite of Geoffrey of Monmouth, (writing in the 12th Century). If Bede mentions a person or an event then they are accepted as part of the story of the English. By contrast, if Geoffrey of Monmouth mentions a person or event, without further corroboration, then historians tend to consider it a story, myth or simply made up by Geoffrey.

But, the truth is not so straightforward. Bede is not without his biases and his sources were not themselves always reliable, nor above accepting myth, legends and miracles as fact. Geoffrey also has access to some, probably, oral traditions so that some (but which?) of his many tales of the Kings of Britain may hold considerable historical information.

Bede’s Influence on English History

Bede followed Gildas (A British Monk writing in the 6th Century) in wondering why God allowed the native Christian Britons to be defeated by the foreign Pagan English. Gildas assumed God was punishing the Britons because of the evil deeds of their so-called Christian Kings. Bede extends this to argue that God is punishing the Britons for not trying to convert the English to Christianity AND by being generally not a great bunch of Christians. God knows that the English, when converted, will be much better Christians than the Britons.

This starts a histographical trend for the English to think of themselves as the chosen people. By contrast, the Britons (Welsh, Scots and Irish) are feckless Barbarians (they thought). Bede concentrates on the English and countless generations of Historians have either left out the Britons, or demeaned them in their histories of England and indeed of Britain.

For example, most histories of Kings, deal only with England and start either with William the Conqueror or Alfred the Great and omit any British, Welsh, Scots or Irish Kings. Except for my book on the Kings and Queens of Britain, which starts with the largely legendary Kings of Britain, and includes some Welsh and Scottish Kings. To buy it, you will find details of it here.

So Bede is a great historian without whom we would have an even less clear idea about what happened in the centuries following the Roman Period. But also, contributed to an Anglo centric view of history. He was writing in Northumberland at the Monastery of Jarrow, and is more sympathetic to Northumbria than to Wessex, Mercia, and the British Kingdoms.

Bede’s Books

He wrote over 60 books. One was about the theological science of computus. In particular, the dating of Easter. The British Church had one method, the Catholic Church another. This contributed to a series of confrontations between the 2 Churches. And was only finally resolved at the Synod of Whitby in the favour of the Catholic Church.

Bede was instrumental in making Dionysius Exiguus idea of dating from the birth of Christ as the standard AD /BC system. He also thought the Catholic calculation that Jesus was born 5000 years ago was wrong and used the Bible to calculate the more ‘correct’ date was 3952 BC. Archbishop Ussher in the 17th Century took Bede’s calculation and improved it and suggested the proper date was 4004 BC.

For more about Dionysius Exiguus and the division of time, see my post here.

First Written on May 26th 2025