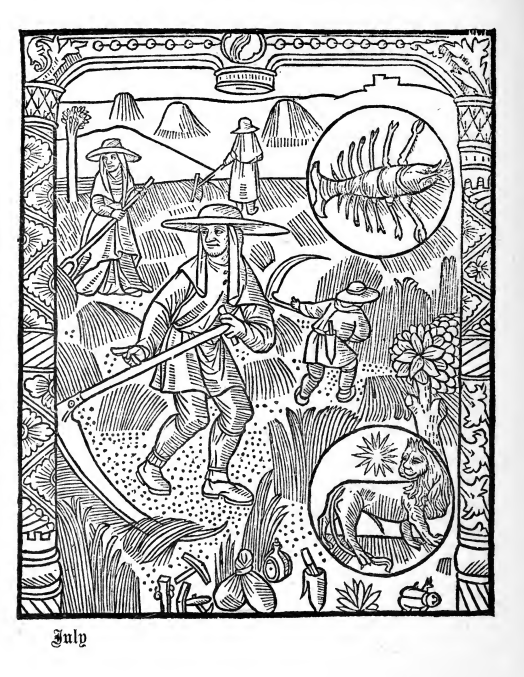

The Feast Days of St John the Baptist (June 24th) and of St Peter and Paul (29th June) What is remarkable is the scale and the expense of the celebrations.

These Saints are some of the most important in the Christian Calendar. John being the forerunner to Jesus and his cousin, and Peter and Paul being the apostles who, more than anyone else, created the Christian Church.

There are also pagan rituals associated with the Feast of St John. Here is an example of French pagan solstice fires:

“They were lit at the crossroads in the fields to prevent witches and sorceresses from passing through during the night; herbs gathered on Saint John’s Day were sometimes burned to ward off lightning, thunder and storms, and it was thought that these fumigations would ward off demons and tumults.”

For more information, have a look at ‘French Moments’ here:

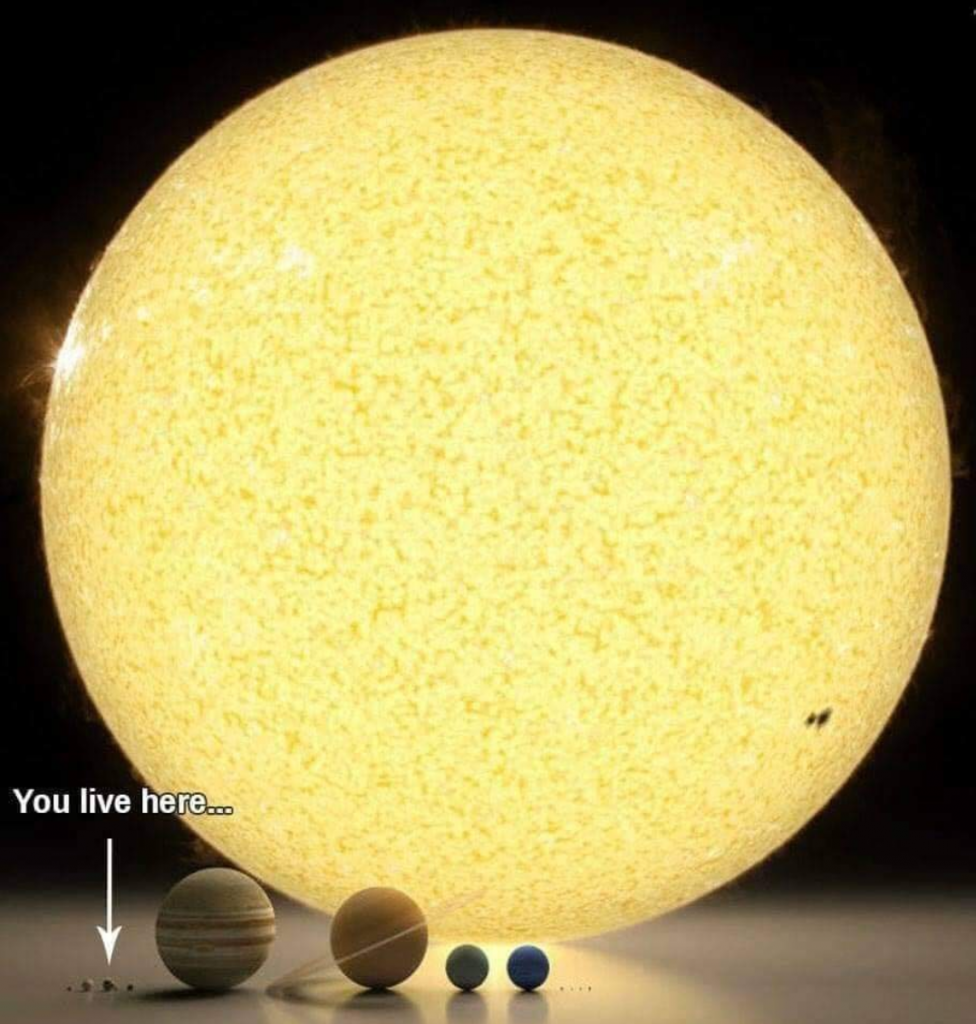

The Feast of St John is often described as being on the Summer Solstice, it isn’t by modern reckoning, but nor is December 25th the Winter Solstice. But they were celebrated as such by Christians, and the Solstice can be thought of as spread over 3 or 4 days (or more if taking into account Solstice Old style). The major events of the sun and the moon were linked into Christian theology and symbolism. Jesus, son of God, would clearly have arrived at the auspicious time of the Winter Solstice. His cousin, John the Baptist, came to tell the world about the coming of Jesus and so his birthday was exactly 6 months before the Summer Solstice.

St John is also special as most Saint’s Days are linked to the day of their death, but June 24th is the birthday of St John. His beheading by Herod is commemorated on 29th August.

St John the Baptist upon Walbrook in the City of London is first mentioned in the 12th Century, burnt down and not rebuilt after the Great Fire of London. The parish was, later, united with St Antholin, Budge Row, The Graveyard survived until 1884 when the District Line destroyed most of the Graveyard and the bones were reinterred below a monument, which can still be seen in Cloak Lane.

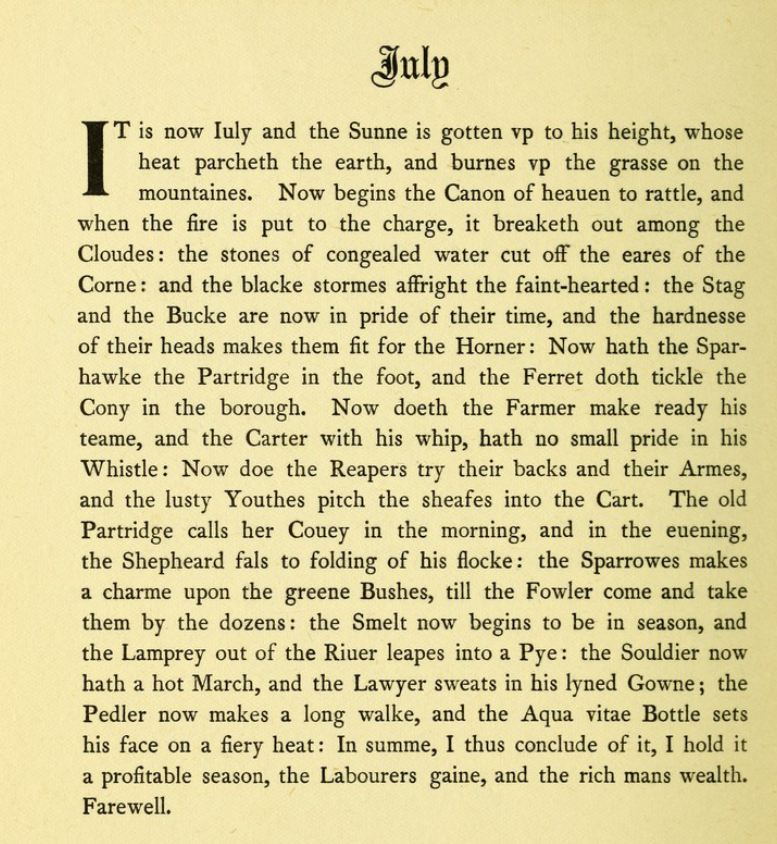

Here is what John Stow tells us about the processions on the night before the feast of St John (24th June) and St Peter and Paul (29th June):

On the vigil of St. John the Baptist, and on St. Peter and Paul the Apostles, every man’s door being shadowed with green birch, long fennel, St. John’s wort, orpin, white lilies, and such like, garnished upon with garlands of beautiful flowers, had also lamps of glass, with oil burning in them all the night; some hung out branches of iron curiously wrought, containing hundreds of lamps alight at once, which made a goodly show, namely in New Fish street, Thames street, etc.

Then had ye besides the standing watches all in bright harness, in every ward and street of this city and suburbs, a marching watch, that passed through the principal streets thereof, to wit, from the little conduit by Paule’s gate to West Cheape, by the stocks through Cornhill, by Leaden hall to Aldgate, then back down Fenchurch street, by Grasse church, about Grasse church conduit, and up Grasse church street into Cornhill, and through it into West Cheape again.

Grasse Church Street is Gracechurch Street.

The whole way for this marching watch extendeth to three thousand two hundred tailor’s yards of assize; for the furniture whereof with lights, there were appointed seven hundred cressets, five hundred of them being found by the companies, the other two hundred by the chamber of London.

Note a cresset is: a ‘metal container of oil, grease, wood, or coal set alight for illumination and typically mounted on a pole’ (Wikipedia).

Besides the which lights every constable in London, in number more than two hundred and forty, had his cresset: the charge of every cresset was in light two shillings and four pence, and every cresset had two men, one to bear or hold it, another to bear a bag with light, and to serve it, so that the poor men pertaining to the cressets, taking wages, besides that every one had a straw hat, with a badge painted, and his breakfast in the mornings amounted in number to almost two thousand.

The marching watch contained in number about two thousand men, part of them being old soldiers of skill, to be captains, lieutenants, serjeants, corporals, etc., wiflers, drummers, and fifes, standard and ensign bearers, sword players, trumpeters on horseback, demilances on great horses, gunners with hand guns, or half hakes, archers in coats of white fustian, signed on the breast and back with the arms of the city, their bows bent in their hands, with sheaves of arrows by their sides, pike-men in bright corslets, burganets, etc., halberds, the like bill-men in almaine rivets, and apernes of mail in great number;

there were also divers pageants, morris dancers, constables, the one-half, which was one hundred and twenty, on St. John’s eve, the other half on St. Peter’s eve, in bright harness, some overgilt, and every one a jornet of scarlet thereupon, and a chain of gold, his henchman following him, his minstrels before him, and his cresset light passing by him, the waits of the city, the mayor’s officers for his guard before him, all in a livery of worsted, or say jackets party-coloured, the mayor himself well mounted on horseback, the swordbearer before him in fair armour well mounted also, the mayor’s footmen, and the like torch bearers about him, henchmen twain upon great stirring horses, following him.

The sheriffs’ watches came one after the other in like order, but not so large in number as the mayor’s; for where the mayor had besides his giant three pageants, each of the sheriffs had besides their giants but two pageants, each their morris dance, and one henchman, their officers in jackets of worsted or say, party-coloured, differing from the mayor’s, and each from other, but having harnessed men a great many, etc

John Stow, author of the ‘Survey of London‘ first published in 1598. Available at the wonderful Project Gutenberg: ‘https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42959/42959-h/42959-h.htm’

First published june 2023 republished in 2024