We left the Peasants following Richard II out of Smithfield, going home after the murder of their leader, Wat Tyler. If you want to refresh your knowledge see the three links to my ‘Almanac of the Past’ at the bottom of this post. I want to follow the events from Mile End to August in St Albans. They give a good overview of what the Revolt was all about, and how the authorities responded to it.

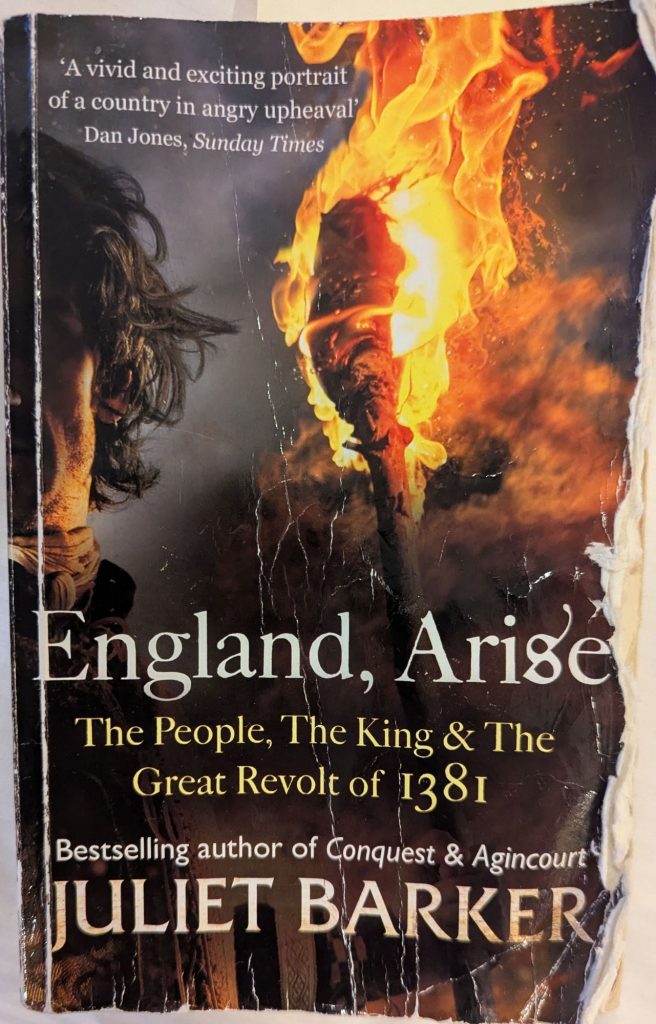

My source is ‘England, Arise. The People, the King & the Great Revolt of 1381’ by Juliet Barker. I have been reading it for some time. It is very comprehensive and shows how much more there was to it, than the three or four days in London.

The aftermath of Mile End

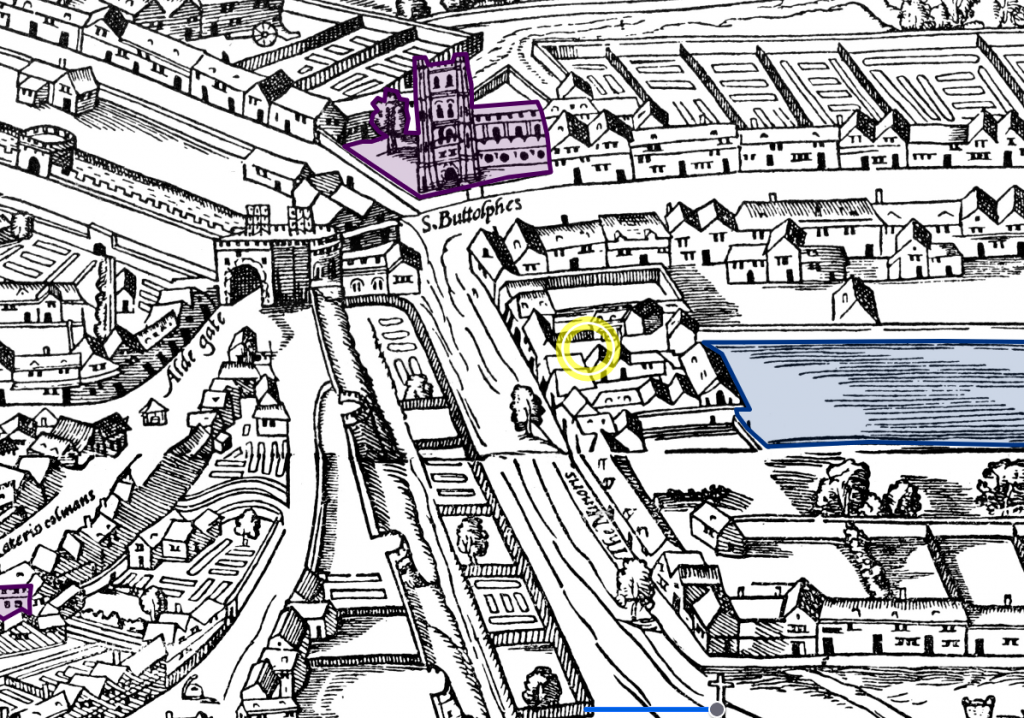

Rebels from St Alban came back from the meeting with King Richard II at Mile End on June 14th. William Grindecobbe, who was identified as one of their leaders, travelled from St Albans to attend the meeting at Mile End on the day of the meeting. Barker suggests he travelled on the morning of the event. Google tells me it is a 23 mile walk, and would take 9 hrs at least. So, he either travelled by horse or travelled down the day before?

The evidence suggests his interest in the Mile End meeting was to get charters from the King to free the people of St Albans from the onerous feudal demands of the Abbot of St Albans. Grindecobbe is said to have ‘knelt to the King six times’ to obtain ‘letters patent’ for St Albans. Remember, the young King was about 14 at this time, and went to the meeting without his senior government advisors. This leads some to believe he was sympathetic to the demands of the Peasants.

Grindecobbe then returned to St Albans with news of the liberation of the town from its feudal shackles. He left behind Richard Wallingford to collect further royal documentation of the momentous changes in society granted at Mile End.

These included:

the right of St Albans to have borough status

to pasture their animals freely within the town boundary

to enjoy fishing, hunting and fowling rights

to be able to use their own hand-mills rather than take their wheat to the Abbots expensive mill

Some of the monks of St Albans (including the Prior) were so scared of the rebels that they fled to Northumberland (to a daughter church of the Abbey).

The townsfolk, on their return from London, dismantled gates and enclosures protecting the Abbey’s woodland. They demolished a disputed house, and attacked houses of Abbey officials.

Next morning which is said to be the 15th of June (the Smithfield Day) the St Albans people assembled, swore an oath to be faithful to each other. They caught a live rabbit and fastened it to the Town Pillory. Thus, demonstrating their right to hunt on Abbey Lands. They went to the Abbey Prison and freed the prisoners, except one who they beheaded and added his head to the Pillory.

Richard Wallingford arrived from London with a banner of St George, erected it in the Town Square and marched to the Abbot to present the King’s letters he had obtained.

The letters ordered the Abbot to hand over certain charters made by ‘our ancestor King Henry’ concerning the various issues listed above (and others.)

Faced with documents signed with the King’s Privy Seal the Abbot had to comply. The rebels burned various of the deeds and charters in the market-place. But they felt the Abbot was still withholding an important document, which the Rebels said was illuminated with 2 capitals letters one in gold and another in blue.

The history of the dispute between towns people and Abbot went back to Domesday and possible beyond to the time of King Offa. Or to put it another way the peasants thought they were restoring rights that had been illegally taken from them by the Abbot.

For example, in 1251 Henry III had granted legal freedoms to the men of St Albans. But the Abbey had used its power to circumvent this much desired status. It obviously rankled bitterly with the men of St Albans. And here we have to remember those men were not just peasants, there were a number of substantial citizens who stood with the Rebels. They were standing up for their rights against an oppresive Abbot.

An example of the arrogance of the Abbots is found in a previous dispute about the use of hand-mills. The Abbot had confiscated all the hand-mills used by the townsfolk and paved his parlour with them! Now, the Peasants dug the hand-mills up and took them home.

Over the next few days the Abbot was forced to confirm the abolition of villein status, and many other measures enshrined in the feudal system. For example, he had to confirm the legality of the locals using hand-mills rather than paying to use the Abbots Mill. The Rebels were scrupulous in documenting the new freedoms. This suggests that their destruction of legal documents was not a sign of hatred of written records but their dislike of their use in oppressing them.

What is clear is that at this point of time, the Rebels and the authorities believed the King had indeed liberated peasants and towns people from feudal exactions.

Reaction

After the Rebels had scattered following the Smithfield confrontation, the Government eventually regained its nerve. Or to put it another way, maybe the older heads finally persuaded the young King Richard II that he was wrong to support the Rebels in their demands for reforms to the feudal system.

On 29th June, Sir Walter atte Lee, arrived in St Albans with 50 men-at-arms, and a large group of archers. He was an experienced soldier, ex Member of Parliament, and a Justice of the Peace. By this time St Albans was at peace. But Lee restored the Abbey’s supremacy over the town’s people, and arrested Grindecobbe and other leaders of the Town. However, the Town stood solid and juries refused to accept their leaders had done anything wrong. Grindecobbe was released.

However, the King and his Chiel Justice Tresilian arrived. They had been in Essex putting the revolt down. On 2nd July Richard agreed to reverse all the concessions and charters he had conceded at Mile End. Why he changed his mind we do not know.

In St Albans Tresilian did not bother about the niceties of the legal system. He made it clear that people who protected the rebels would suffer their fate. Grindcobbe was thrown back in prison on July 6th, and Grindecobbe and 14 others from St Albans were hanged, drawn and quartered. The hand-mills were returned to the Abbot who had them set back in his parlour floor, and all the reforms were reversed.

On the 13th July John Ball was tried at St Albans possibly having been captured in Coventry. He was executed, beheaded and quartered on July 15th. His four quarters were sent to 4 cities to be displayed. We know very little about Ball’s role in the uprising and most of what we think we know was made up by his enemies. He may have been a simple honest preacher, pointing out the unfairness of the oppressive system. Not perhaps the revolutionary firebrand, preaching a form of primitive communism as portrayed by Walsingham.

His execution was at St Albans presumably because this was where the King and his Chief Justice were.

The Rebels at St Albans were hung in the woods they had briefly gained access to. Their bodies were ordered to be hanged ‘until they lasted’. But a local man cut them down and buried them. On August 3rd the authorities ordered that the town’s people find the bodies, dig them up ‘with their own hands’ and hang them up again but this time with chains.

Over a year later, on September 3rd 1382, the King, following a plea from his Queen Anne gave license for them to be taken down and buried.

80 other rebels in St Alban’s were sentenced and imprisoned.

Scenes like this were repeated all over England.

Chief Justice Tresilian

He became a leading member of King Richard’s Government. Richard became increasingly unpopular as he grew up. And Tresilian, on 17th November 1387 was found guilty of Treason by the Lords Appellant (who were trying to restrain Richard’s misused power).

Wikipedia tells us his fate:

‘He fled and on 19 February 1388, he was discovered hiding in sanctuary in Westminster. He was dragged into court with cries of ‘We have him!’ from the mob and, as he was already convicted, was summarily executed, being hanged naked before his throat was cut.’

Can’t help feeling he got what he deserved.

Richard II

Richard himself was eventually forced to abdicate (1399) and was supplanted and then murdered by Henry Bolingbroke. There is some evidence that Londoners remembered his role in the repression of the Revolt.

Bolingbroke was saved during the events of 1381 by the intercession of a couple of the Rebels who evidently felt the young son of John of Gaunt should not suffer for the sins of his dad. One of these people was a woman who was identified as a leader of the Revolt, showing women did not have a passive role in it.

First published August 2025

![By JanesDaddy (Ensglish User) - English Wikipedia - [1], CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1663124](https://www.chr.org.uk/anddidthosefeet/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/1280px-Eels_1385-1024x768.jpg)