I just tried to book a visit to see the Stone of Destiny, at Perth Museum. But I was told it was closed until at least the end of August. The reason being that a case had been damaged. A quick search revealed this notice that an Australian had attacked the case containing the Stone with a hammer. They are now repairing the Case, and double checking the condition of the stone, which is thought to be undamaged. The Stone is well protected in a special room of the Museum. But, until now, those booking to see it are not searched. So I imagine that this will become more formal in future.

Below is my post of 2024, updated on March 30th 2025.

New Home for the Stone of Destiny

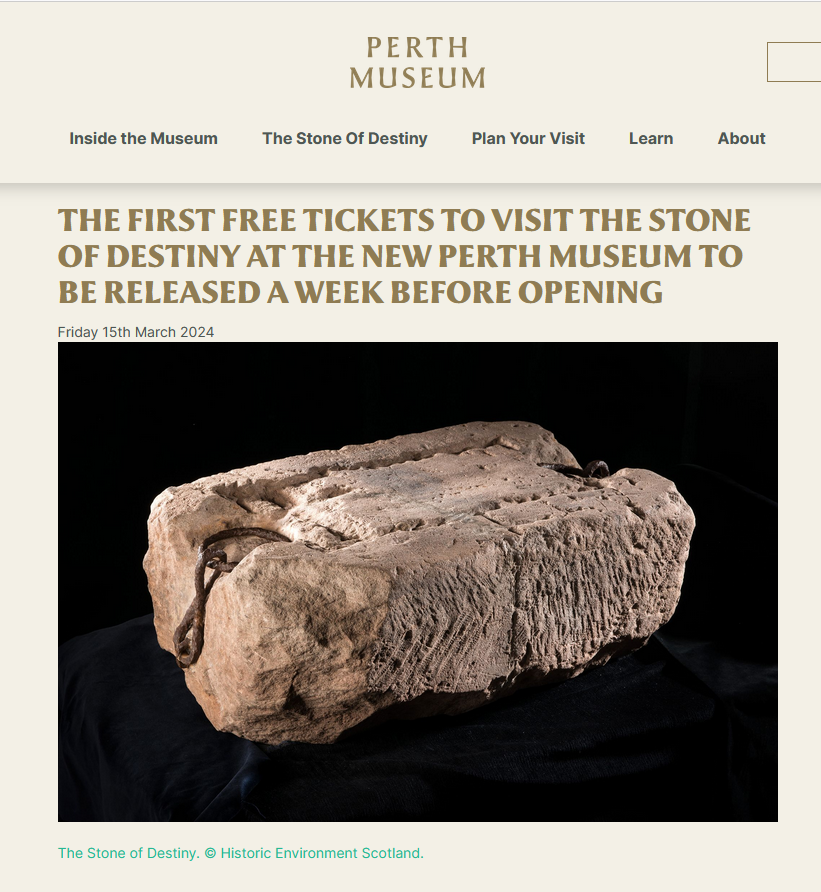

Last year, the Stone of Destiny was set up in its new permanent place. The Stone was unveiled in a room at the centre of the redeveloped Perth Museum, in Scotland. This is near to its ‘original’ home at the Palace of Scone.

The Museums Association reported:

‘£27m development project ….funded by £10m UK government investment from the £700m Tay Cities Deal and by Perth & Kinross Council, the museum is a transformation of Perth’s former city hall by architects Mecanoo.’

As well as the Stone of Destiny, the Museum has Bonnie Prince Charlie’s sword and a rare Jacobite wine glass. Both on public display for the first time. This is the first time the sword has been in Scotland since it was made in Perth in 1739. https://perthmuseum.co.uk/the-stone-of-destiny/. Since I first wrote this I have visited about 5 times. Entry is free but needs to be booked. It is held in a separate structure in the open space at the heart of the Perth Museum. There is an excellent-animated introduction, and then the doors open and the Stone is revealed in a glass cabinet. It is very effective.

The Stone of Destiny in the Modern Era

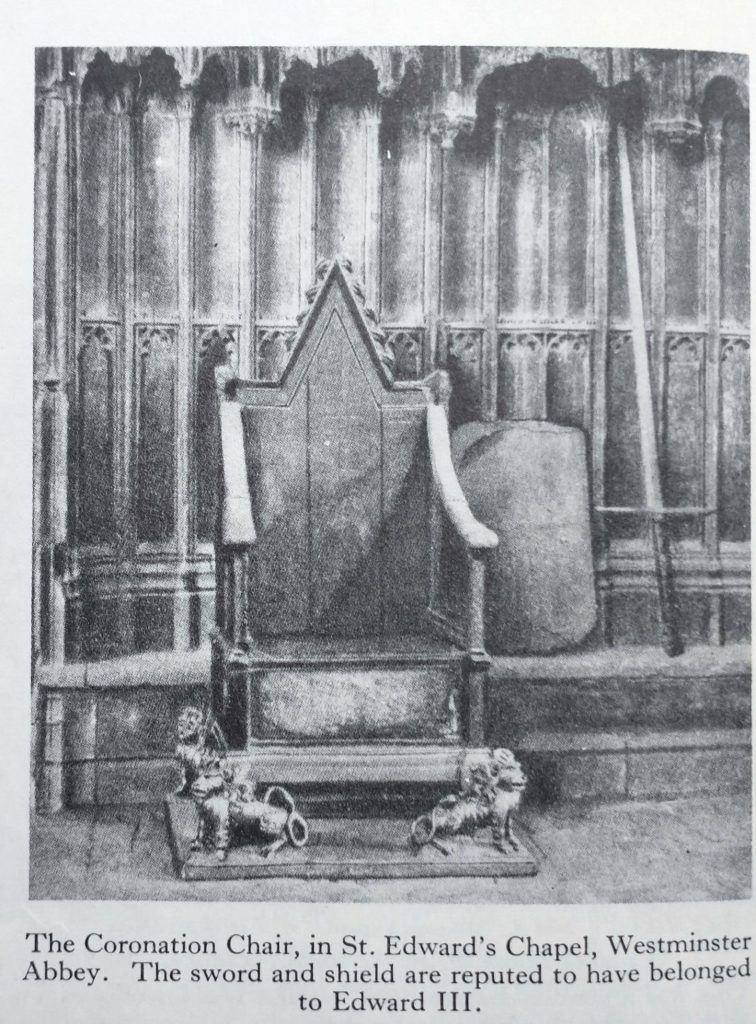

Before Perth, the Stone was in London for a brief visit for the Coronation of King Charles III (6 May 2023) . It was put back, temporarily under the Coronation Chair. Before that it was on display in Edinburgh Castle. Tony Blair’s Labour Government sent it back to Scotland as a symbol of the devolution of power from Westminster. This was on the occasion of the restoration of the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh in November 1996. Until then the Stone was under the Coronation Chair, where Edward I put it after he stole it (1296) from Scone. Virtually every English and British King has been crowned upon the Stone of Scone.

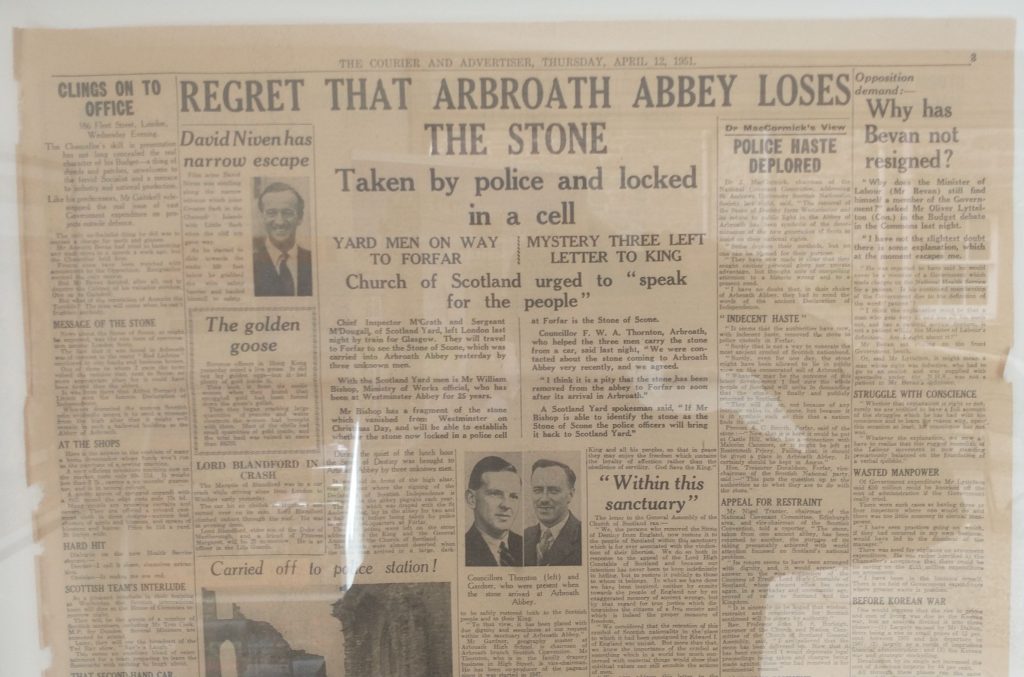

However, the Stone had a brief holiday in Scotland in 1950/51. Four Scottish students removed it from Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1950. After three months, it turned up at the high altar of Arbroath Abbey. It was briefly in a Prison Cell, then returned to Westminster for the Coronation of Elizabeth II.

Declaration of Arbroath

I’m guessing the-would-be liberators of the Stone, thought Arbroath was the most suitable place to return it. For it was the Declaration of Arbroath which is the supreme declaration of Scottish Independence from England.

Following the Battle of Bannockburn the Scots wrote to the Pope of their commitment to Scotland as an independent nation. They said:

“As long as a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be subjected to the lordship of the English. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself”

The Pope agreed and Scotland remained independent until voluntarily joining England in the United Kingdom in 1707.

For an analysis of the Stone of Scone please look at my post here.

The Stone of Destiny at Scone Palace

Before Edward 1 stole the Stone, it was at Scone Palace. Here most of the Kings of Scotland were crowned, including Macbeth (August 14, 1040).

Those who attended the coronation traditionally shook their feet of all the earth they had brought from their homelands. This over the centuries, grew into Boot Hill, aka Moot Hill. So the mound represents the sacred land of Scotland. 42 Kings were crowned upon its soil on its Stone. (but not Mary Queen of Scots she and her son were crowned at the Chapel Royal of Stirling Castle).

Where was the Stone of Destiny before Scone?

Before Scone, it was, possibly, in Argyllshire where the Gaelic Kings were crowned. Their most famous King was Kenneth MacAlpin. He united the Scots, Gaelic people originally from Ireland, the Picts, and the British. And created a new Kingdom which was originally called Alba, but became Scotland.

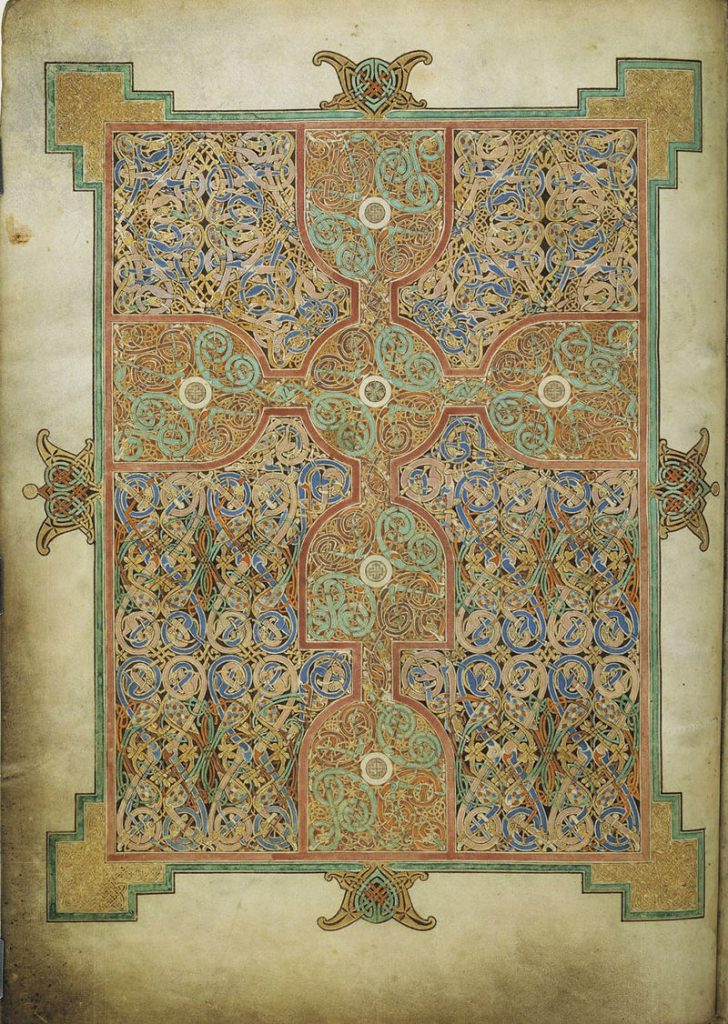

MacAlpin was the first king to be crowned on the Stone at Scone in 841 or so. He made Scone the capital of his new Kingdom because it was a famous Monastery, associated with the Culdees, an early sect of monks. MacAlpin brought sacred relics from Iona to sanctify the new capital. And Scottish Kings were by tradition crowned at Scone and buried on the holy Island of Iona.

Legend has it that the Scots bought the Stone from Ireland when they began to settle in Western Scotland (c500AD). The Scots, it is said, got the Stone from the Holy Land. Jacob lay his head on the stone to sleep. He had a dream of Angels ascending and descending a ladder to Heaven. Jacob used the stone as a memorial, which was called Jacob’s Pillow (c1652 years BC).

Fake, Copy or Genuine?

But, questions about the Stone remain. Firstly, would the Monks of the Abbey meekly hand over the stone to a raging King Edward I? Sacking the Abbey was one of the last events of Edward’s failed attempt to unite the two countries. Isn’t it more likely that they hide the original and gave him a fake?

Secondly, was the Stone brought to Scone from Western Scotland in the 9th Century? Or was it made in Scone?

These questions of doubt are based on the assumption that the Stone is made of the local Scone sandstone. If it were brought to Scone from somewhere else, it would be in a different type of stone, surely? So, either it was made in Scone, possibly for MacAlpin’s Coronation or the Monks fooled the English into taking a copy. The English would then have been crowning their Monarchs on a forgery.

Ha! Silly English but then the Scots have spent £27m on the same forgery.

Before bringing the stone to Scone, Historic Environment Scotland undertook a new analysis of the stone. This confirmed:

‘the Stone as being indistinguishable from sandstones of the Scone Sandstone Formation, which outcrop in the area around Scone Palace, near Perth‘.

It also found that different stone workers had worked on the stone in the past. It bore traces of a plaster cast being made. It had markings which have not yet been deciphered. There was copper staining suggesting something copper or bronze was put on the top of it at some point in its life.

So it seems the Stone of Destiny was made in Scone. The simplest explanation is that it was made for MacAlpin in the 9th Century. But it does not rule out that it is a copy given to Edward I. But if this is the case it is still an awesome relic of history as so many Kings and Queens, Scottish and English, have been crowned upon it.

For more about MacBeth and St Margaret of Scotland see my post here:

First published in 2024, republished in 2025