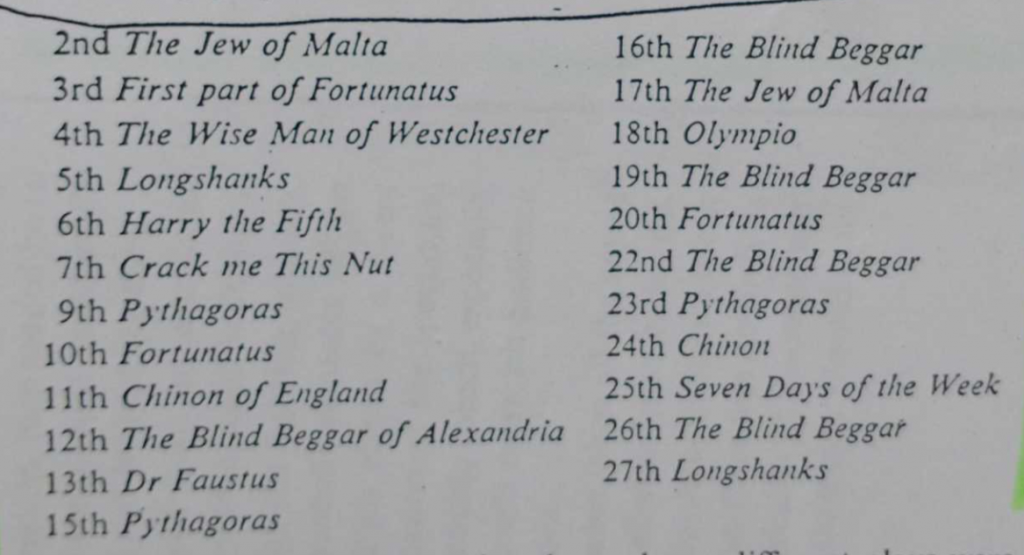

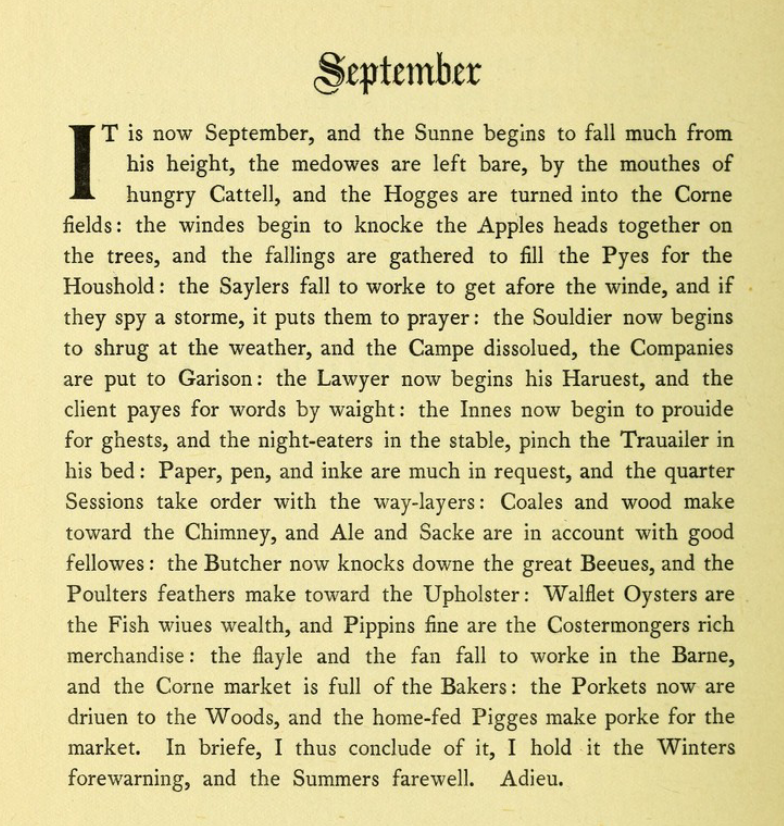

This year the Stratford mop festival was on the 11th and 12th October. I was in Stratford for it, and the centre of the Town is crowded with a cacophany of shooting galleries, stalls selling toffee apples, candy floss, burgers and all things bad for you. And a fun fair. Quite raucous, but they leave Henley Street free of it which is probably a good idea. Nothing at all sophisticated, or literary or dramatic, or folkloric. Just a good old-fashioned fun fair in the middle of the town. Below I tell the story of my discovery of the Mop.

Last year, at this time, I was on my way to Stratford-upon-Avon Railway station, I saw the sign above sign, but had no idea what on earth a Mop was.

So I put it to the back of my mind as I took the train to Henley-in-Arden. My interest in the town began because Shakespeare was born in Henley St in Stratford, and his mother was called Mary of Arden. So, naturally, I wanted to find out about Henley-in-Arden. To turn curiosity to action, it took our Tour Coach Driver telling me he lived there and that it was a pretty but small town.

I had a free afternoon from my duties as Course Director on the ‘Best of England’ Road Scholar trip, so I got on the very slow train to Henley-in-Arden. One of the first stops was Wilmcote, where Mary Arden’s House is. I visited two years ago, when I was astonished to find it was a different building to the one I had visited in the 1990s.

In 2000, they discovered they had been showing the wrong building to visitors for years! Mary Arden’s House was, in fact, her neighbour Adam Palmer’s. And her house was Glebe Farm. On that visit, I walked from Stratford on Avon to Anne Hathaway’s Cottage then to Mary Arden’s House and back to Stratford along the Stratford Canal – a lovely walk if you are ever in the area.

The train route to Henley is through what remains of the ancient forest of Arden. The forest features in, or inspired, the woody Arcadian idylls which feature in several of Shakespeare’s plays, particularly the Comedies. ‘As You Like It’, for example, is explicitly set in the Forest of Arden, as this quotation from AYL I.i.107 makes clear:

Oliver: Where will the old Duke live?

CHARLES: They say he is already in the Forest of Arden, and a many merry men with him; and there they live like the old Robin Hood of England: they say many young gentlemen flock to him every day, and fleet the time carelessly as they did in the golden world.

Henley-in-Arden turns out to be a quintessentially English little town full of beautiful timber framed buildings and a perfect Guildhall.

Further down the road is a lovely Heritage Centre full of old-fashioned and DIY Information panels. And that is not a criticism, it provided a very enjoyable visit full of interesting stuff and which gave me a couple of snippets of information I have not seen anywhere else.

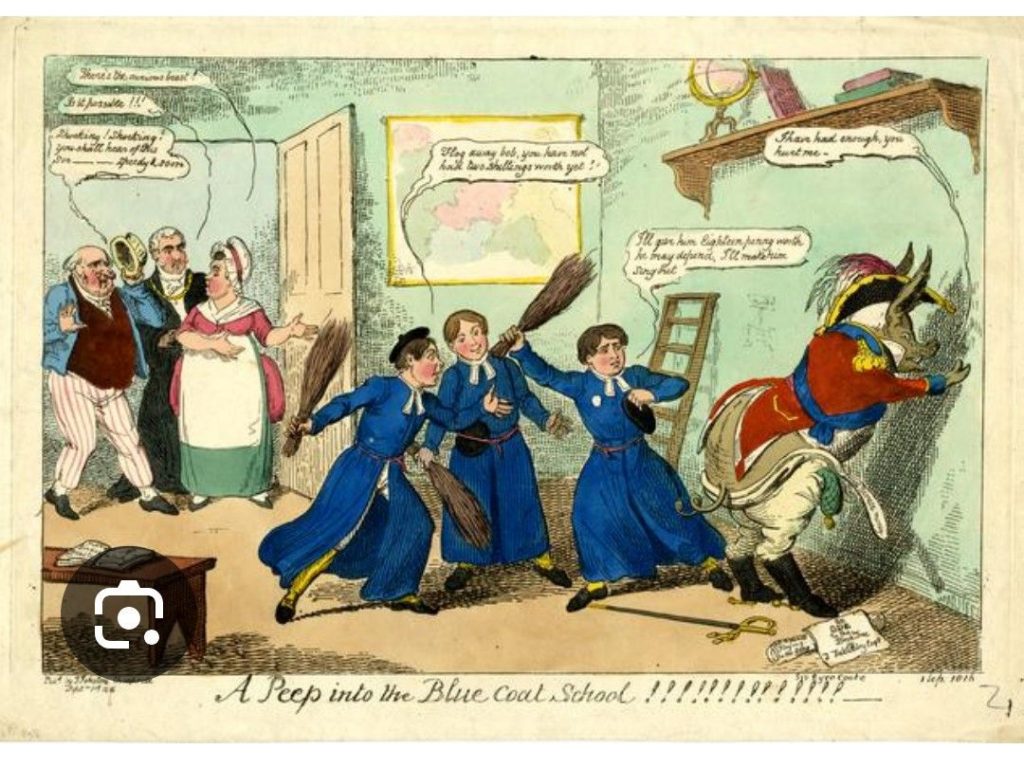

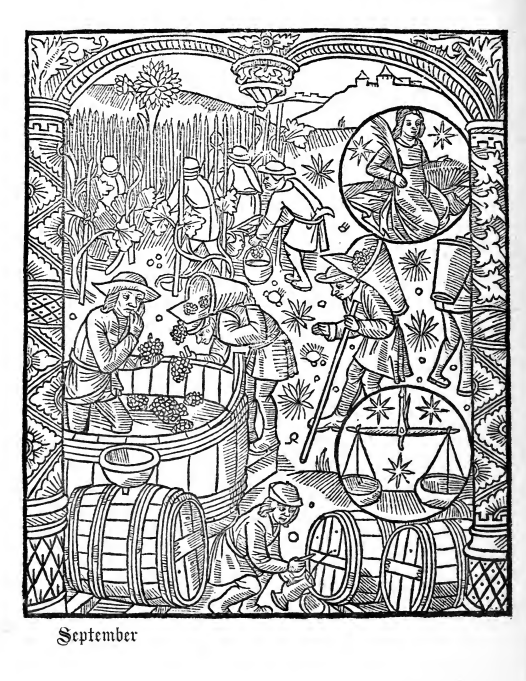

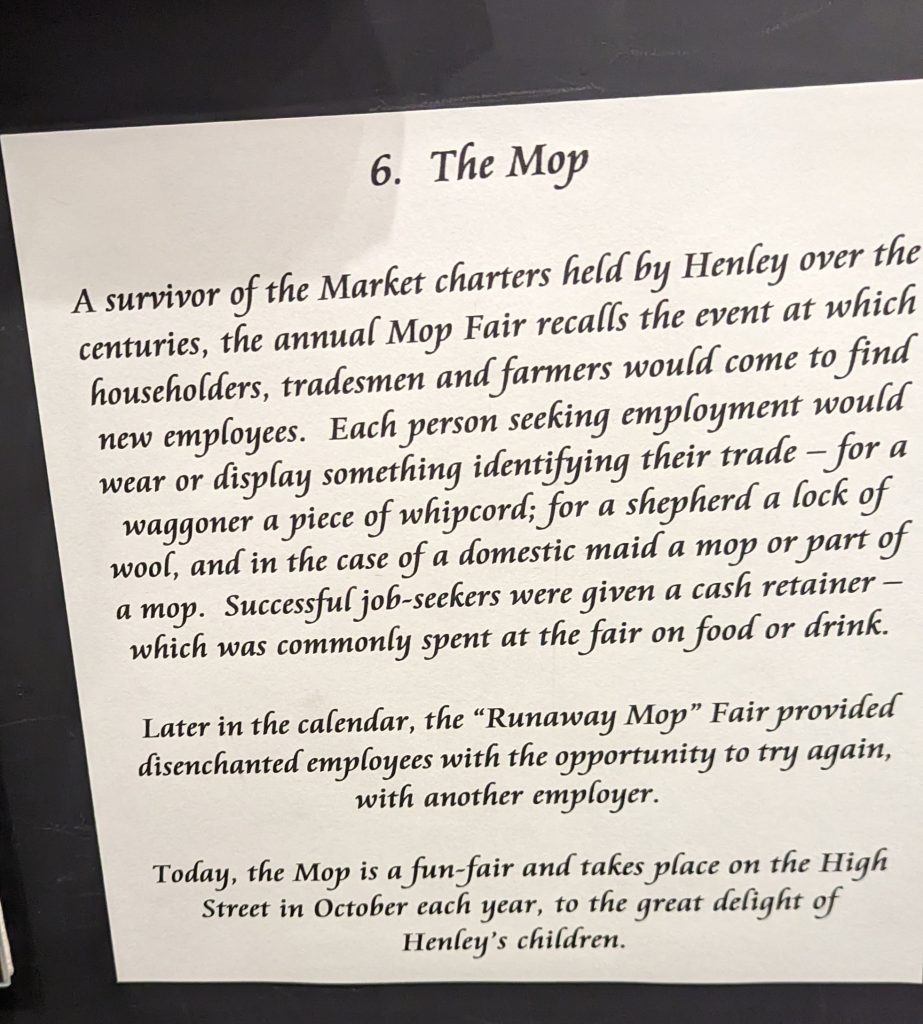

So, to get back to the signpost for the Mop, I was delighted to find a panel dedicated to the Henley Mop. A mop turns out to be a hiring fair. Think of Gabriel Oak in Hardy’s ‘Far from the Madding Crowd’. His attempt to become an independent farmer destroyed when his sheepdog runs amok and sends his sheep over a cliff to their doom. So he takes his shepherd’s crock to the hiring fair or Mop as they are known in the Midlands. There, potential employers can size up possible employees and strike mutually agreed terms and conditions. And Gabriel becomes the shepherd for the delightful and wilful Bathsheba Everdene.

So, a shepherd would take his staff, or a loop of wool; a cleaner her mop (hence the name of the fair), a waggoner a piece of whipcord, a shearer their shears etc. Similarly, in the Woodlanders (by Thomas Hardy) the cider-maker, Giles Winterborne, brings an apple tree in a tub to Sherborne, to advertise his wares.

The retainers thus employed would be given an advance and would be engaged, normally, for the year. So there was quite a widespread moving around of working people to new jobs and often new housing. Not quite how we imagine the past?

The perceptive among you will have noted the bottom of the sign in Stratford which advertised the ‘Runaway Mop’. This was held later in the year, so that employers could replace those who ran away from their contracts, and where those who ran away could find a better, kinder or more generous boss.

Also of interest to me was the panel about Court Leets and Barons. These were the ancient courts which dealt with, respectively, crime and disorder, and property and neighbourhood disputes. Henley still has its ancient manorial systems in use, at least ceremonially. The Centre shows a video of a cigar-smoking Stetson-wearing large rich American arriving at the Guildhall to take over duties as lord of the manor after purchasing the title.

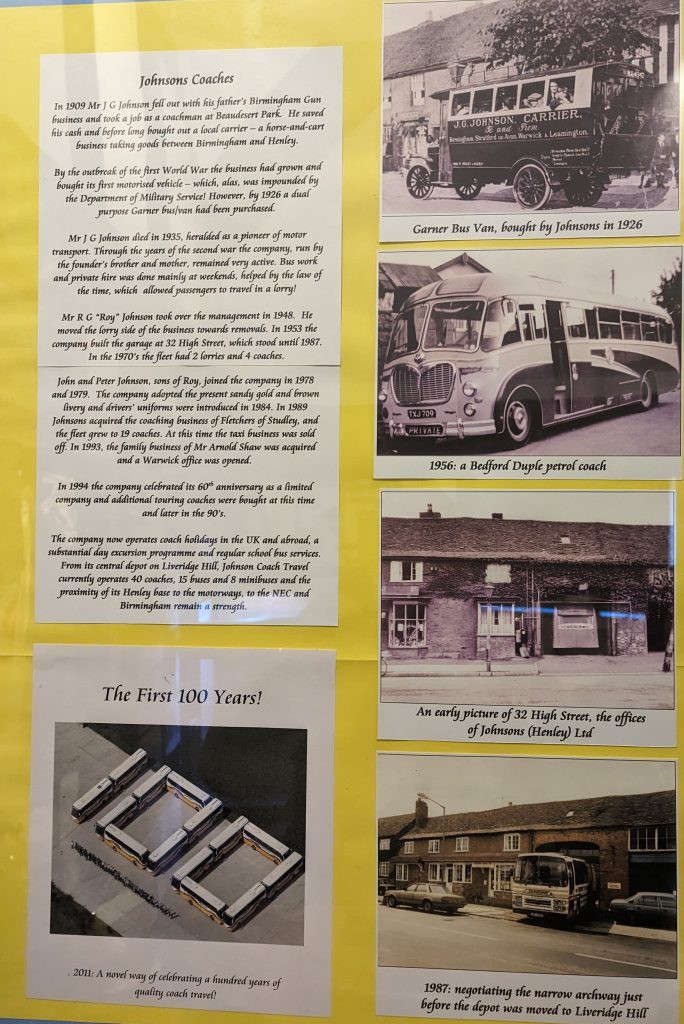

There was another panel of great interest to me as it told the history of Johnson’s Coach Company which was taking my group around England. And it was a delight to discover that it has a history that can be traced back to 1909 in Henley. I conveyed this information to our group on the following day as we toured the Cotswolds. Curtis, our driver, was able to update the panel and told us that the family were still involved with the firm, which is still operating from the area. He said the two brothers who run the company come in every working day and do everything they require of their drivers to do; i.e. they drive coaches, clean coaches, sweep the floors and generally treat their staff like part of a big family. I should have asked him whether he got his job at the Mop, while holding a steering wheel in his hands!

First published in 2023 updated 2024