Canterbury Pilgrimage

Tonight, I am leading my annual Canterbury Tales Virtual Pilgrimage. This is the day Chaucer’s pilgrims leave London to ride to Canterbury. (For more details or to book look here.)

At the beginning of the prologue, Chaucer gives clues as to the date. They go when April showers and Zephyrus’s wind is causing sap to rise in plants, engendering flowers. It is also when Aries course across the sky is half run.

The pilgrims are accompanied by Harry Bailly who is the landlord of the Tabard Inn in Southwark. He was a real person and a fellow Member of Parliament of Chaucer.

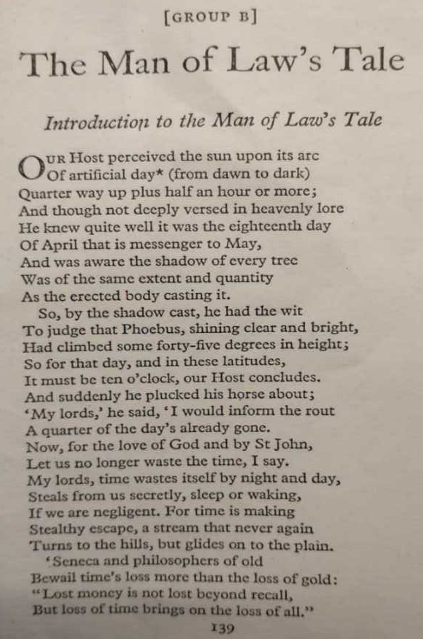

He is jolly and quite knowledgeable. In the Man of Law’s prologue we get a glimpse of Harry time telling in the days before clocks.

Telling the Time

Chaucer mentions ‘artificial day’ and this is a reference to the way days were divided into hours. There were twelve hours in the daylight part of the day, and twelve hours in the dark night. So in the winter daylight hours were short, and in the summer long.

Romans used water clocks. King Alfred used candles marked into hours. Harry Bailly knows how to tell the time by the height of the Sun. Harry tells the pilgrims it’s about time they got underway. Here is an extract:

Essentially, he is telling the time by the length of the shadows. The illustration of the mass clock at Jane Austen’s Church at Steventon shows how easy it was to tell the time by the sun.

The first mass clock I noticed was at St James’ Cooling in Kent. Dickens used this in Great Expectations, where Pip’s brothers and sisters were buried. Once you find one mass clock, you suddenly discover them everywhere!

Telling the time, before mechanical clocks, was not complicated. The basic unit is the day and the night, and we can all tell when the dawn has broken. The Moon provides another simple unit of time. The month’s orbit around the Earth is roughly every 29 days. The new, the crescents and full moons provide a quartering of the month. For longer units, the Earth orbits around the Sun on a yearly basic. But it is easily divided into four, the winter solstice; the spring equinox, the summer solstice and the autumn equinox.

Nature’s Way of Time Telling

But there were other ways of marking days in the calendar, with natural time markers marked by, for example, migrating birds, lambing, and any number of budding and flowering plants such as snowdrops, daffodils and elm leaves:

When the Elmen leaf is as big as a mouse’s ear,

Then to sow barley never fear;

When the Elmen leaf is as big as an ox’s eye,

Then says I, ‘Hie, boys” Hie!’

When elm leaves are as big as a shilling,

Plant, kidney beans, if to plant ’em you’re willing;

When elm leaves are as big as a penny,

You must plant kidney beans if you mean to have any.’

In my north-facing garden, I have my very own solar time marker. All through the winter, the sun never shines directly on my garden. Spring comes appreciably later than the front, which is a sun trap facing south. But in early April, just after 12 o’clock the sun peeks over the block of flats to the south of me. It finds a gap between my building and the converted warehouse next door. For a short window of time, a shaft of a sunbeam brings a belated and welcome spring.

New Light on Thomas Becket’s Window at Canterbury

Recent research has revealed the true story behind stained glass windows at Canterbury which had been reassembled wrongly.

The story is told here:

And if you cannot get through the pay wall here:

First published in 2023, revised 2025

Discover more from And Did Those Feet

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Lovely